By Hunter Williams and Bruce Spear

A version of this article first appeared in BRINK on February 25, 2019.

Tariffs distort markets, impacting the cost of imported finished goods and key inputs. These costs are likely to be passed on to consumers, reducing demand. That, in turn, may force companies to rethink their entire supply chains or manufacturing location. Harley-Davidson, for example, says tariffs will cost them $100-$120 million in 2019 (excluding an increase in metal costs), and is forcing them to move production to Thailand to avoid tariffs on sales in Asian and European markets.

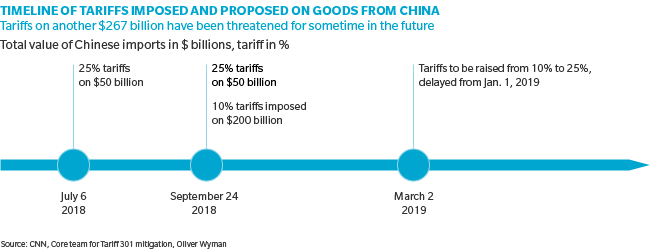

In the United States, the first round of 10-percent tariffs on $200 billion worth of Chinese products (announced in September) is impacting prices on a broad set of consumer products—such as televisions, electronics, furniture, clothing, air conditioners, washing machines, cars, and beer – which may only accelerate if trade negotiations break down and trigger an increase to 25 percent. Another $50 billion worth of goods is already subject to tariffs at that rate, and President Trump has even threatened 25 percent tariffs on another $267 billion worth of (unspecified) imports, “if China takes retaliatory action against our farmers or other industries” (see “Timeline of Tariffs Imposed and Porposed on Goods from China”). The deadline for trade negotiators to reach an agreement has been extended twice, but the Trump administration has hinted that even if negotiations stave off additional tariffs, the existing 10-percent tariff structure may remain in place.

Many American companies—including Walmart, Gap, Coca-Cola, and General Motors—have said that tariffs could force them to raise prices. The Alliance for American Manufacturing, for example, estimates that 70-80 percent of products sold at Walmart are sourced from China. Apple’s 1st quarter revenues were down 5 percent year-over-year and more than 7 percent below expectations, due to lower iPhone sales in China and concerns over a US-Chinese trade war. Caterpillar, on the other hand, raised prices in 2018 to offset a $200 million hit from tariffs and had its best 3rd quarter ever.

It’s not just the imposition of tariffs that is harmful to businesses, but the uncertainty surrounding their magnitude and the counterparty’s response. The agricultural industry in the United States has been promised $12 billion in subsidies to offset the impact of current tariffs. If tariffs are increased from 10 to 25 percent, will the subsidies also increase or will farmers (and consumers) absorb the pain?

REDUCING NEGATIVE IMPACT OF TARIFFS

Escalation of the current trade dispute would destabilize companies in key industries as well as their supply chains. US companies must act quickly to develop pricing and supply-chain strategies. Do they absorb added costs? Do they pass on increases to consumers? Can they counteract various changes in consumer behavior? A well-considered strategy can protect margins during a time that is certain to produce winners and losers. With this in mind, here are four key questions to address.

1. How exposed am I relative to my competition?

First, calculate your maximum exposure—the impact of an unmitigated absorption of an increase in cost-of-goods-sold (COGS). But understanding the impact on your own company isn’t enough. Research competitors’ supply chains and quantify their exposure vis-à-vis your own. Specifically, calculate the percentage of your competitor’s products that are sourced from China and their relative exposure to the tariffs.

2. How can I mitigate the impact on COGS?

While it can be difficult to fully eliminate the effect on COGS, four mitigation strategies can help offset or soften the impact:

- Seek an exemption. Investigate potential tariff exemptions under Section 301 of the US Trade Act of 1974, which gives the president the authority to limit trade that is “unjustified, unreasonable, or discriminatory.” The tariffs may only apply to a limited set of products, depending on part sourcing and type of fabrication.

- Identify alternative suppliers in other geographies. Consider suppliers, manufacturers, and fabricators based in countries other than China. There is an emerging narrative that, once the dust settles, Southeast Asia may be the prime beneficiary of the US-China trade dispute (Harley’s move to Thailand fits this narrative).

- Assemble or “transform” materials in another region. Avoid tariffs by importing materials from China to another country with zero tariffs, “substantially transforming” them there, and shipping the finished product to the final destination. European and Japanese automakers have used this strategy to offset volatility in exchange rates, as well as to avoid import tariffs.

- Share the burden. Where possible, shift the cost burden to suppliers. This requires understanding which suppliers are likely to absorb some of the impact. Specifically, it requires understanding your relative power in the buying relationship (availability of substitutes, ease of switching, and supplier/customer concentration) and ability to absorb the financial impact (relative margins and balance-sheet strength).

3. If I must pass along price increases, how can I mitigate a decline in demand?

Understanding price elasticity enables you to estimate how a change in price will likely impact demand—if customers defer or avoid purchase, or if they switch to a competitor. Further, determining relative elasticity (one product, such as sofas, may be more price sensitive than another, such as dining room tables) allows you to target the price increases to parts of your business that are best positioned to absorb them.

With this in mind, there are two primary types of elasticity analysis to consider:

- Own-price elasticity of demand. This estimates the impact of a change in price on sales volume. For example, an increase in price may lead customers to defer purchases or avoid them altogether (“we can live with the old sofa another year”). This is most meaningful at the category level for a given market. Price elasticity for individual categories can often be inferred from historical data or market simulation.

- Cross-price elasticity of demand. This estimates the impact of a change in the difference between your price and your competitor’s price on a given product. While non-price factors (such as product features, service, convenience, and available stock) often allow one company to charge more for a similar item, it is the change in that price differential that impacts demand. Robust analysis of past promotions can often shed light on how customers will respond, including their propensity to trade-down to lower-priced offerings. If you anticipate this, you can use elasticity analysis to anticipate where customers will down shift and steer them to lower-priced products with better margins. In these cases, you could proactively structure your assortment to improve margins on less expensive products.

4. How will my competitors respond?

For pure commodity products, it can make sense for more exposed players to be first to market with a price increase and last to market with a price reduction, in order to maximize the effects of expanding margins. However, for products that are not commodities (greater differentiation), not all players are likely to pass on price increases. In these instances, game theory is required to anticipate how competitors might act on their own or respond to your actions.

Given that exposure to tariffs on Chinese imports will vary significantly across companies, less exposed players may see an opportunity to gain share by reducing prices. The result will depend upon the elasticities of demand and relative exposures of industry players.

Conducting a “wargaming” workshop—a role-playing exercise to predict a competitor’s potential actions or reactions—can help an organization get inside the mind of its competitors and deliver a concrete and actionable response plan. When there is a key change in the market that is expected to impact current business, wargaming helps to create the necessary sense of urgency to change strategy.

LONG-TERM UNCERTAINTY IN GLOBAL TRADE

If and when the current trade disputes and tariffs will be resolved remains to be seen. But a trading system hampered by tariffs, administrative red tape, and uncertainty may be the “new normal,” at least for the foreseeable future.

Further, in the current political climate, companies also need to consider that raising prices or reshaping the supply chain may draw unwanted scrutiny. For example, Harley-Davidson received significant negative press after announcing that it would shift production for the European market outside the US, after tariffs on its motorcycles increased from 6 to 31 percent. Companies need to consider not only the immediate “dollars and cents” impacts, but also how their moves may be perceived by the media and in the court of public opinion.

In this unpredictable global trading environment, companies must be prepared to react quickly to sudden changes. How retailers answer these four key questions could indeed make the difference in protecting margins and profits. Developing the right pricing and supply-chain strategies now can help manufacturers and retailers shore up their foundations and better weather the unpredictable and shifting business climate.

Gabe Knapp, a principal in Oliver Wyman’s Dallas office contributed insights and research to this article.