By Tom Cooper, Brian Prentice and David Stewart

This article first appeared in Brink on May 8, 2019.

For two decades, most airlines have stayed out of the business of aircraft maintenance and left the work to third-party providers — or, in recent years, aerospace manufacturers. There were plenty of independent service companies to keep rates relatively stable and ensure enough capacity to accommodate aviation’s needs. But the maintenance, repair and overhaul (MRO) sector has been undergoing a transformation in recent years, and a plethora of pressures and emerging risks is beginning to convince airlines it may be time to get back into the aftermarket —another name for the MRO sector.

In recent months, the industry has seen a spate of announcements by airlines about plans to reinvest in MRO in-house capacity. In most cases, it has been to handle their own needs, but some airlines are also looking to create an increasing source of revenue by offering MRO services to other carriers.

Competitive Squeeze

What changed? First, there are fewer independent MRO providers because of consolidation. With emerging technologies like predictive maintenance, it’s getting more expensive for these firms to stay current. It’s also getting harder to find mechanics capable of repairing the pre-2000 vintage aircraft, as well as those planes produced after the start of the millennium.

The biggest push behind consolidation came from aerospace manufacturing. Over the last few years, aerospace manufacturers have started to expand into MRO and assert their control over the intellectual property (IP) behind engines, components and airframes. This made life tough for smaller MRO providers, leading to consolidation.

Last year, the two biggest aircraft manufacturers, Airbus and Boeing, indicated they expect to exponentially increase their MRO business over the next several years. At the 2018 Farnborough International Airshow, Airbus said it would triple its revenue from MRO to $10 billion in a decade. Boeing, already with a sizable revenue of more than $16 billion in 2017, said it planned to hit $50 billion in revenue over the next 10 years. Clearly, the aftermarket is never going to be the same.

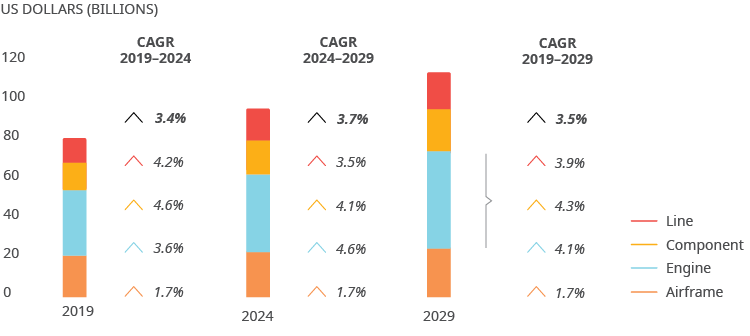

Future Growth Of MRO

Source: Oliver Wyman

Rising Prices

In Oliver Wyman’s 2018 MRO survey, 78 percent of industry executives said they expected aerospace manufacturers to expand their aftermarket presence over the next three years. A majority reiterated that expectation this year.

Most respondents in 2018 also suggested manufacturers, including airframe and engine makers, would do that by leveraging control over existing IP and licensing to boost market share. The question wasn’t asked in this year’s survey.

While there has been some competitive price-cutting on specific parts, the manufacturers’ move into the aftermarket is expected to push up prices over the long run and reduce the number of competitors. Already, some carriers are reporting higher prices. And it was exactly the risks of rising prices and reduced leverage in negotiations that prompted some airlines to rethink their outsourcing strategy on MRO.

The second big threat that airlines see ahead — which is also the opportunity that makes MRO so attractive — concerns how fast aviation is expanding and expectations for growth of the aftermarket itself.

According to the 2019-2029 Oliver Wyman Global Fleet and MRO Market Forecast, the global fleet of aircraft will grow 42.5 percent by 2029, when it will exceed 39,000 aircraft. With it, there will be a concomitant increase in aftermarket spend, up 41.4 percent to $116 billion.

Insufficient Capacity

The problem is whether the industry has the capacity to accommodate the growth. One of the biggest question marks is labor supply: There just aren’t enough trained mechanics and other aviation maintenance technicians as baby boomers retire and too few millennials are recruited. Based on Oliver Wyman calculations, the shortfall will expand to more than nine percent in 2027, just as the fleet is reaching its peak size.

There is also a potential shortage in airframe and engine MRO capacity. To avoid being affected by these shortages, airlines reckon it may be best to have a sufficiently big in-house crew and facilities to handle a chunk of their own internal needs.

The pressure may be the greatest in Asia, where the growth will be the biggest because of the burgeoning middle classes in nations like China and India. That helps explain why two of the announcements for expanding MRO came from Air Asia and Malaysian Airlines.

Survey: Reasons Why Airlines Are Moving Into MRO

Source: Oliver Wyman analysis

Some Never Left

Of course, some airlines, such as Delta, Lufthansa and Air France-KLM, never left the maintenance business. They already have a track record as service suppliers to other carriers. Here, the shortage of supply—both capacity and labor—and the rising demand are encouraging the parent airline to grow that side of the business.

On Feb. 21, Delta unveiled a new jet engine test facility, reportedly the largest in the world. The airline said it hopes to expand its maintenance unit, Delta TechOps, by $1 billion over the next five years. A key part of this expansion focuses on adding newer Rolls-Royce engines to its existing engine maintenance portfolio, a decision reflecting the need to ensure capacity and greater supplier choice for Delta, as well as an effort to increase third-party revenue. It also provides necessary maintenance capacity to handle new engines.

Airlines are caught between a contracting number of providers and mechanics and a significant growth in demand. With questions about the adequacy of capacity and the loss of leverage against manufacturer-controlled MRO, carriers have had little choice but to practice a little risk management that could turn into new revenue.