Editor's Note: This article was originally published in Volume 3 of the Oliver Wyman Health Innovation Journal. Download a PDF of this article here and read the full collection of articles here.

Health isn’t something addressed only in a doctor’s presence. “Health” is where patients live, who they communicate with, and how happy and safe they are. Social and economic factors – such as education, employment, income, family and social support, and community safety – account for up to 40 percent of a population’s health. Physical environment factors (such as the quality of someone’s environment and how it makes him or her feel) account for another 10 percent.

Social determinants of health (SDOH) – factors like income, literacy, education, and culture that shape someone’s health – were once just another trending phrase. Now, they’re something organizations are putting serious money behind. For example, a $650 million Section 1115 waiver for North Carolina’s Medicaid program – a pilot program approved by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services – is expected to provide services like housing, nutrition counseling, ride-sharing, and legal assistance for eligible individuals experiencing risk factors like homelessness or interpersonal violence. This announcement comes on the heels of multiple health plans and provider organizations announcing their own SDOH initiatives, including:

- Geisinger’s Fresh Food Farmacy program, which provides patients with healthy food to empower them to manage medical conditions through diet and lifestyle changes.

- Health Care Service Corporation’s (HCSC) foodQ pilot, a healthy food delivery service for people in areas where fresh food is hard to come by.

- University of Pittsburgh Schools of the Health Sciences’ Homeless Continuum program, whose services like assessment, outreach, and 24-hour on-call support help the homeless, mentally ill, and/or substance abusers.

- Humana’s Bold Goal initiative, which tracks people’s “bad” physical and mental days over a 30-day period, simultaneously screening patients for factors like whether they have access to inexpensive, healthy food, and how lonely they feel. In 2016, they noticed a 3.1 percent drop in people’s “unhealthy” days across markets in Kentucky, Tennessee, Florida, Louisiana, and Texas, reportedly seeing this improvement because of investments in things like helping people manage their anxiety levels during an emergency, and ensuring food delivery services have a friendly point person between company and client.

Organizations Want to Redesign Patients' Environments, But are They Setting Realistic Expectations?

Despite what may seem like straightforward logic – providing people with stable housing, healthy food, and transportation should improve their health – the data don’t all point to success. For instance, data from a 2018 JAMA article showed a patient cohort with access to free ridesharing missed almost the same number – 36.5 percent versus 36.7 percent – of primary care appointments as a cohort without access to free ride-sharing.

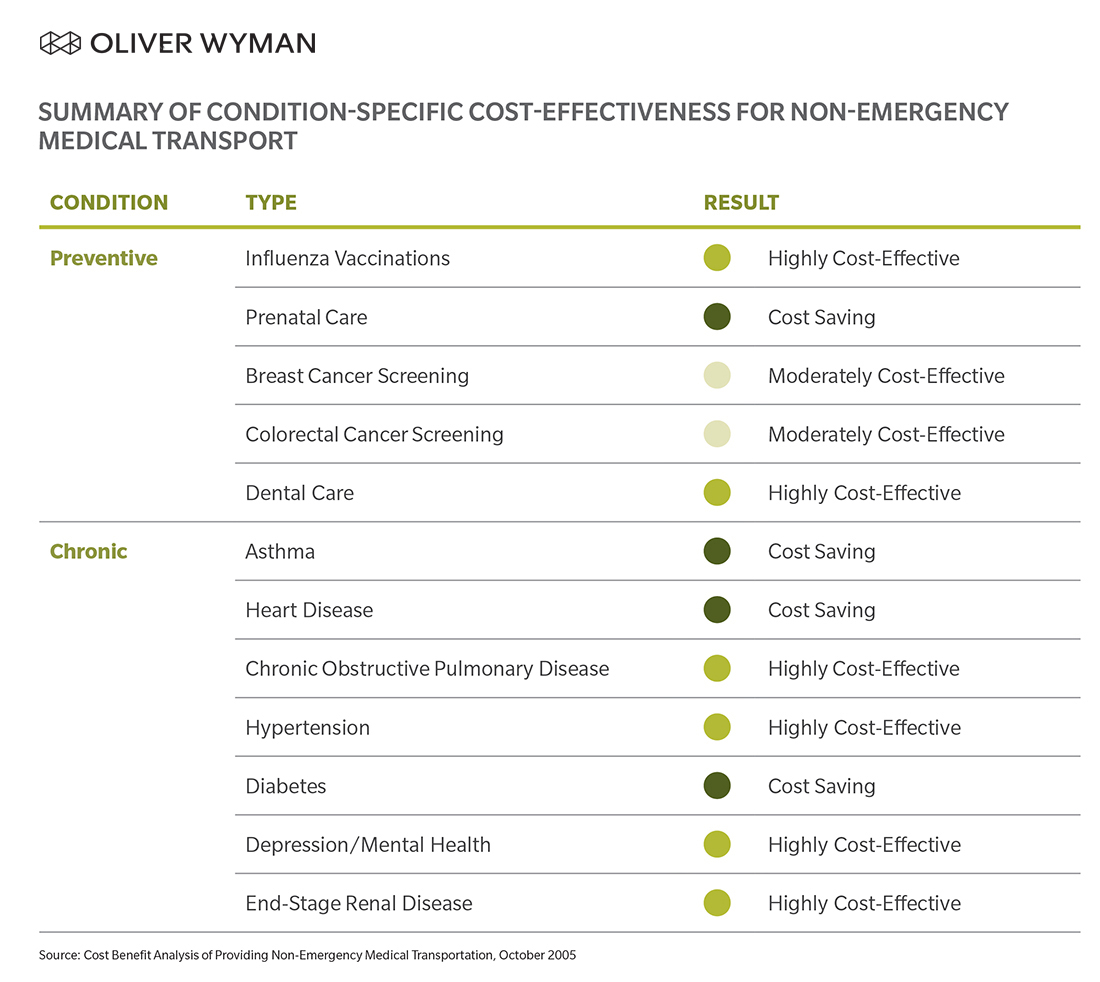

Similar investigation by the Altarum Institute demonstrated cost savings generated by SDOH programs varied largely depending on condition. While the provision of non-emergency medical transport (through a ridesharing service or otherwise) was cost-effective, it only saved money for those conditions studied a third of the time. (See Exhibit 1.) In this example, it’s noteworthy that cost-effectiveness is indicative of sufficient improvement in quality of life, life expectancy, or both. Similar studies focusing on other services including food and housing yield comparable results.

EXHIBIT 1

Companies looking to expand patients’ access to nutritious food, for instance, must consider the social-emotional needs of complex patient populations. Even something as simple as offering healthy food delivery for the homeless means addressing a range of questions often only tangentially related to traditional care delivery, including:

- Where should packages for people living in transitional housing be delivered?

- What type of service should it be – should the food be fresh, frozen, or packaged?

- How do you know people are buying foods that benefit their health? Is there a way to monitor or limit consumer choice? Should there be?

More organizations are, for example, learning why it’s important to help someone who wants to go to the doctor, but physically can’t, and doesn’t know how to ask for help. This is big news. But a one-size-fits-all SDOH approach that doesn’t address patients’ realities or personalize offerings isn’t the answer.

Yet it’s the industry norm.

It’s very encouraging the industry is extending the boundaries of traditional healthcare and taking into consideration the full scheme of social support required by those truly in need. But, for these initiatives to take root and not be dismissed as yet another flash in the pan, the healthcare industry must be careful and thoughtful in rolling out SDOH support.

The question to always keep in the back of our minds isn’t, “Does this work?” It’s “Will people actually do this thing?" Action – not reaction – drives positive social and emotional change for all.

Four Steps for SDOH Impact

So, what does this mean? Should plans shy away from SDOH investment? Not necessarily. Should pilots require, say, multiyear, double-blinded studies to prove benefits don’t just look good on paper? Not necessarily. But…there’s a need to manage SDOH provisions appropriately so value is generated for members, patients, plans, and providers. Here are four specific steps plans and providers can take to ensure their SDOH programs and investments bear fruit:

1. Prioritize members and services. While social services can be used by almost everyone, plans and providers should be thoughtful about which individuals they provide certain services to.

2. Coordinate provision of SDOH services. Typically, individuals who need social support require multiple forms of such support. The various services offered should be well-coordinated (either in person or virtually) and encompass various medical services as needed. If, say, food security is an issue for someone with congestive heart failure, it may be advisable to provide low-sodium food to facilitate some of his or her dietary goals.

3. Utilize the community. Not everything has to be provided by plans or providers – nor should it be. There are plenty of community-based organizations – like religious groups and institutions – that provide access to social services. It’s just a question of knowing what’s provided, understanding how to access it, and coordinating various services once received.

4. Track and monitor usage to fail fast and continuously improve. Use of services needs to be monitored. Was food consumed? Did transportation lead to fewer missed appointments? Did the provision of housing reduce emergency room admissions? Based on these observations, organizations can decide what to continue, what to sunset, and how to alter services so they’re of maximal use for individuals.

We believe everyone deserves a chance at a healthy life. “Health” often involves things beyond the “healthcare” bubble that need addressing – food insecurity, social isolation, and transitional housing, among many others. These factors have enormous impact on a person’s ability to be, and stay, healthy. By approaching SDOH with contemplation and analysis, health plans, providers, and community organizations can ensure precious resources target those most in need, or those most likely to respond. This way, the healthcare system can do well by doing good.

Spotlight Q&A | Esther Dyson, SDOH Champion

Q: Tell us about Way to Wellville and how it addresses SDOH.

A: Wellville is a non-profit national project that works to answer this question: If investing $100 in cultivating SDOH yields $200 in lower costs and better outcomes, shouldn’t individuals and communities double down on efforts? At Wellville, we’re working to help five small communities actually implement the theoretical findings around SDOH. All these things “work” if they actually happen, but “providing access to solutions” is different from “creating an environment where people can (and do) actually take advantage of them.” In short, “access to” doesn’t mean “effective use of,” unless you add in a lot of supporting fabric.

Wellville is a team of six people; we aren’t working alone. Our team is coaching community members to do it – because unless they build it and own it themselves – whatever “it” is won’t last long. We’re helping local partners implement programs across five communities nationwide in areas like obesity, diabetes management, and mental health. In Muskegon, Michigan, for instance, our partners are facilitating access to healthy food for low-income residents, like connecting more people with farmers’ markets and providing grants to local health/food nonprofits. But that also means making the food available conveniently – at the right times and the right places. Like running cooking classes, but also offering child care so more parents and caregivers can take advantage of these classes, and so on.

Q: What lessons have you learned regarding the successes and failures of SDOH pilots and programs thus far?

A: Well, for starters, don’t run pilots! What makes any initiative successful is making it long-term – not a program, but an institution – and embedding it deeply into the community so it complements other institutions. For example, imagine if caseworkers were directly connected to those who run housing, or if pharmacists knew where local food banks are, and so forth. People face multiple problems at a time, so they need multiple sources of support at a time. We’re slowly helping communities build the fabric between programs, which is as important as the programs themselves. Most programs “work,” but are operated as pilots or innovations, not as fundamental, built-to-last community affordances. Some early examples are the Muskegon YMCA’s diabetes prevention program, now scaling seriously, and operating in schools, churches, and other community locations.

And Hello Family, a collection of intertwined family-support initiatives in Spartanburg, South Carolina. To make significant impact, we need to build something lasting, not just run a program until money runs out.

Q: What guidance can you share with the healthcare community looking to make an impact with SDOH programs?

A: Think long-term and bigger picture. Find allies to help advance programs. Don’t worry about competition. Share information. There’s so much data out there, and this data only increases in value when you share it with others.