It may sound contradictory to suggest that protecting nature and climate is necessary for economic growth, but that is clearly the case in the Middle East and Northern Africa where the expansion of desert threatens the region’s sustainability. Already, the World Economic Forum has labelled the MENA region as one of the most water-scarce regions in the world, with 12 of the Earth’s 17 most water-stressed nations.

Admittedly, the drying up of the region preceded the burning of fossil fuels for energy by several millennia: the Sahara Desert was tropical as little as 6,000 years ago, for instance. But over the past few decades, there has been a noteworthy acceleration in the desertification because of a combination of commercial and industrial development and climate change. This has led to the faster-than-expected loss of arable land and wetlands.

Desertification not only endangers the region’s biodiversity and the remaining forests; it threatens food security and raises the potential for a scarcity of freshwater. The World Bank has concluded that MENA faces the greatest expected economic losses from climate-related water scarcity, estimated at between 6% and 14% of the region’s gross domestic product by 2050.

In other words, if the region’s economies are to remain vital, governments and industries must be proactive about protecting the area’s still rich natural capital.

New report on nature

What is natural capital? The term refers to the regional inventory of renewable and non-renewable resources, including plants, animals, air, water, soils, and minerals. A multitude of economic activities rely on the region’s natural capital, such as agriculture, fishing, food production, fashion, pharmaceutical, construction, mining, tourism, and recreation. In fact, some $44 trillion, or more than 50% of the world’s economic output, is either highly or moderately dependent on the environment. That means threats to the environment are ultimately threats to the global economy.

Oliver Wyman in collaboration with the World Government Summit recently released a report on Nurturing Natural Capital. In it, we outline ways business leaders and governments can begin what will be a daunting and expensive mission to save the MENA’s natural capital.

Public policy initiatives

Many governments in the region have been responding. The UAE has launched a nationwide plan to plant 100 million mangroves by 2030. Today, mangroves can protect shorelines, improve water quality, provide nursery grounds for terrestrial and aquatic species, remove carbon from the atmosphere, and create opportunities for recreation and tourism.

At the same time, Saudi Arabia is leading conservation efforts for Red Sea corals with giga-projects in restoration and protection, including the Coral Research & Development Accelerator Platform which fast-tracks research and development that targets coral conservation. Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Qatar, Bahrain, and Kuwait are also all participating in national water security campaigns that stretch through 2030. Meanwhile, the Saudi Green Initiatives, inaugurated in 2021, have set targets that will have a positive effect, such as protecting 30% of its terrestrial and marine area by 2030 and planting 10 billion trees across the country (with more than 600 million expected to be planted by 2030). The Kingdom has also established the Middle East Green Initiatives to help the rest of the region, with targets such as planting another 40 billion trees across the rest of the Middle East.

This is all so encouraging, but most of the activity to date has been driven by governments, with private enterprises tending to stay on the side lines. Companies have tended to focus their efforts on climate, reducing emissions, and adding green products to their portfolios. Yet addressing nature’s needs is also an efficient way to reduce emissions.

For instance, besides destroying habitats, deforestation also significantly increases emissions because of the carbon trees absorb and store. When forests are cut and burned, the trees release tons of carbon dioxide, which increases emissions and ultimately temperatures. The loss of trees also makes climates drier because the moisture stored by the leaves and other parts of the tree are no longer released into the atmosphere. Thus, adding trees or limiting their elimination would mean more moisture and fewer emissions.

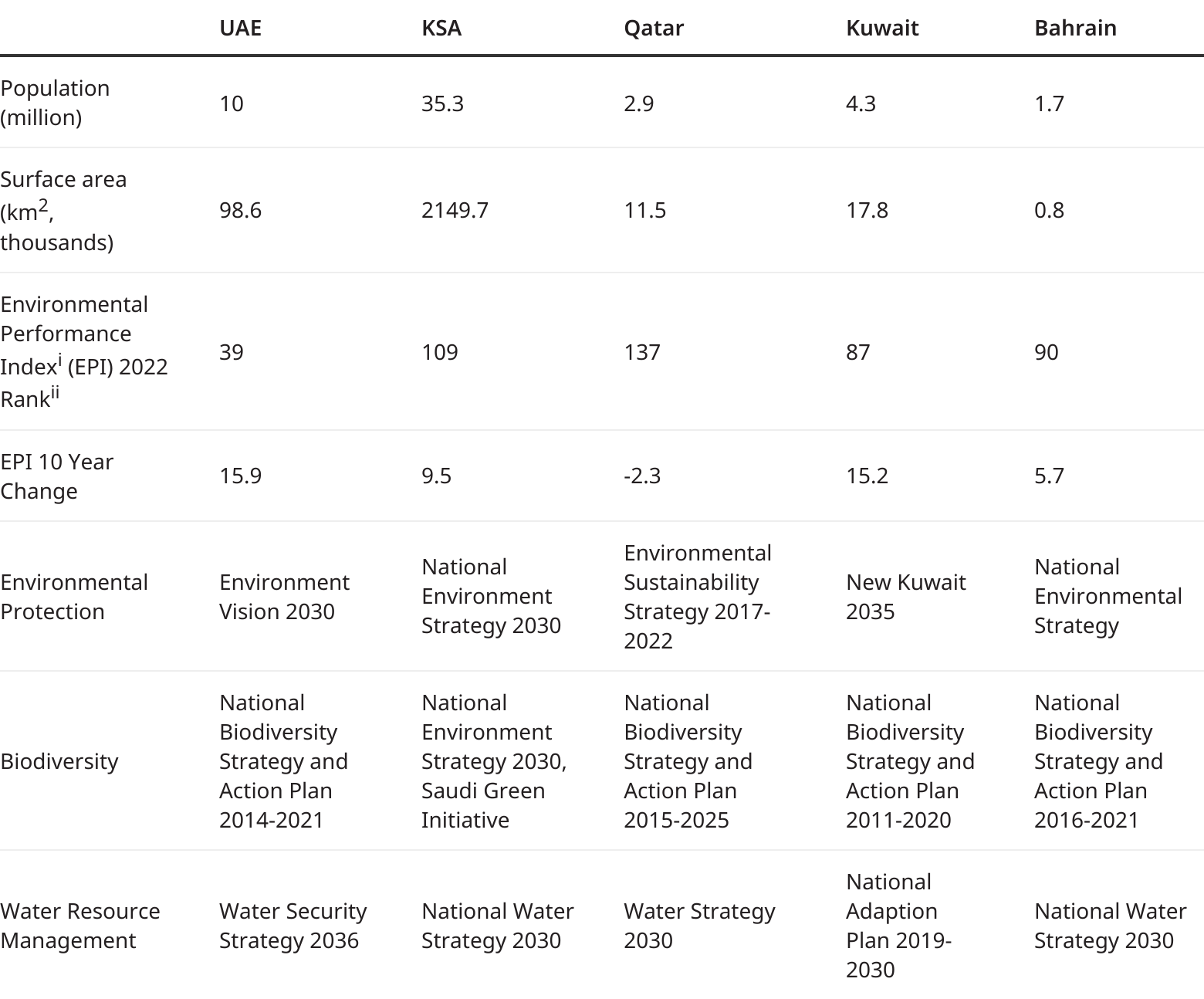

Exhibit 1: Examples of regional environmental protection efforts

i The index provides a data-driven summary of the state of sustainability using 40 performance indicators across 11 categories, covering biodiversity, water management, environmental health, and climate change

ii Rank out of 180 countries

Source: World Bank, Convention for Biological Diversity (CBD), Yale Environmental Performance Index (EPI), KSA Ministry of Environment, Water, and Agriculture (MEWA), Saudi Green Initiative, New Kuwait 2035

Climate effects

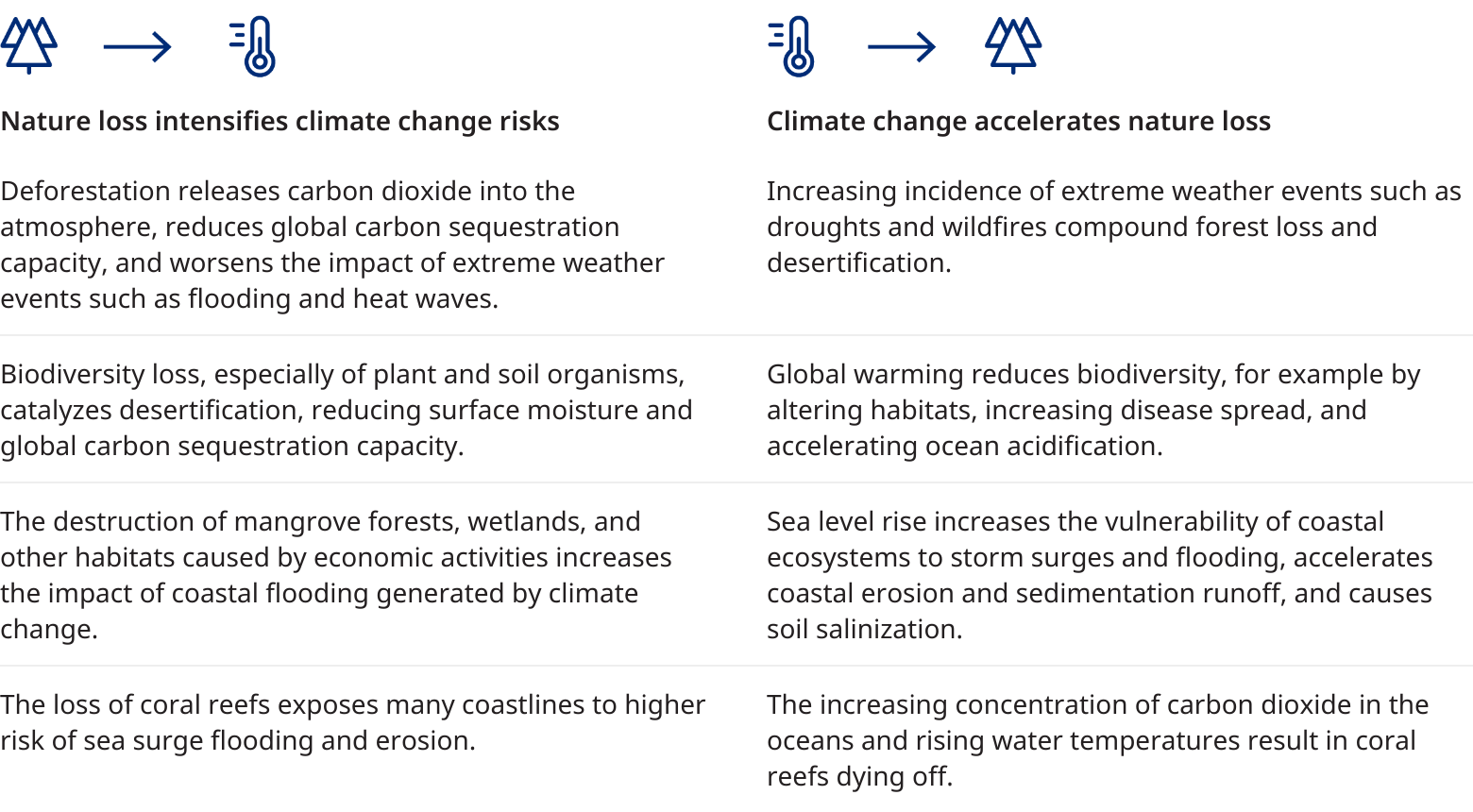

Just as loss of nature contributes to climate change, so too does climate change, a leading driver of nature loss, aggravate the threats to nature. It’s a vicious cycle that is slowly killing the planet. That’s why the establishment of a nature-positive economy with solutions that recognize the impact on nature is essential for the global economy’s transition to net zero.

In Nurturing Natural Capital, we provide an overview of guidelines issued by the Taskforce on Nature-Related Financial Disclosure, which help companies craft policies that protect nature. Right now, frameworks around nature and ways to protect it are less advanced than those available around the planet’s changing climate. With climate, there is one ultimate target: the reduction of greenhouse gas emissions. Protecting nature requires governments and industries to address so many diverse, although interconnected, elements — biodiversity, deforestation, pollution, clean water, clean air, and land and sea use.

It is vital that government, government-owned entities, and sovereign wealth funds set an example, create awareness, and drive momentum for the private sector’s involvement. A first step is requiring strong financial disclosure around emissions and nature to enable transparency and accountability.

Exhibit 2: How nature loss and climate change reinforce each other

Source: Arctic Institute, Climate Policy Initiative, Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, Millennium Ecosystem Assessment, World Wide Fund for Nature, European Sustainable Phosphorus Platform, US Environmental Protection Agency

The need for incentives

The key to engagement is also creating an enabling environment that encourages — in fact, rewards — corporate efforts. Companies should be incentivized to act through grants and tax incentives from government as well as support from major lenders who can help finance nature-positive projects.

In fact, much of the necessary momentum can be driven by financial institutions. As risk managers of the economy, they can and should play a critical role by shifting capital away from nature-negative outcomes by making capital more expensive or unavailable.

The bottom line for the Middle East and for the global economy: nature cannot be ignored. We must begin today to start turning our risks into opportunities — or face the loss of hundreds of thousands of species over the coming years, not to mention endangering our own.