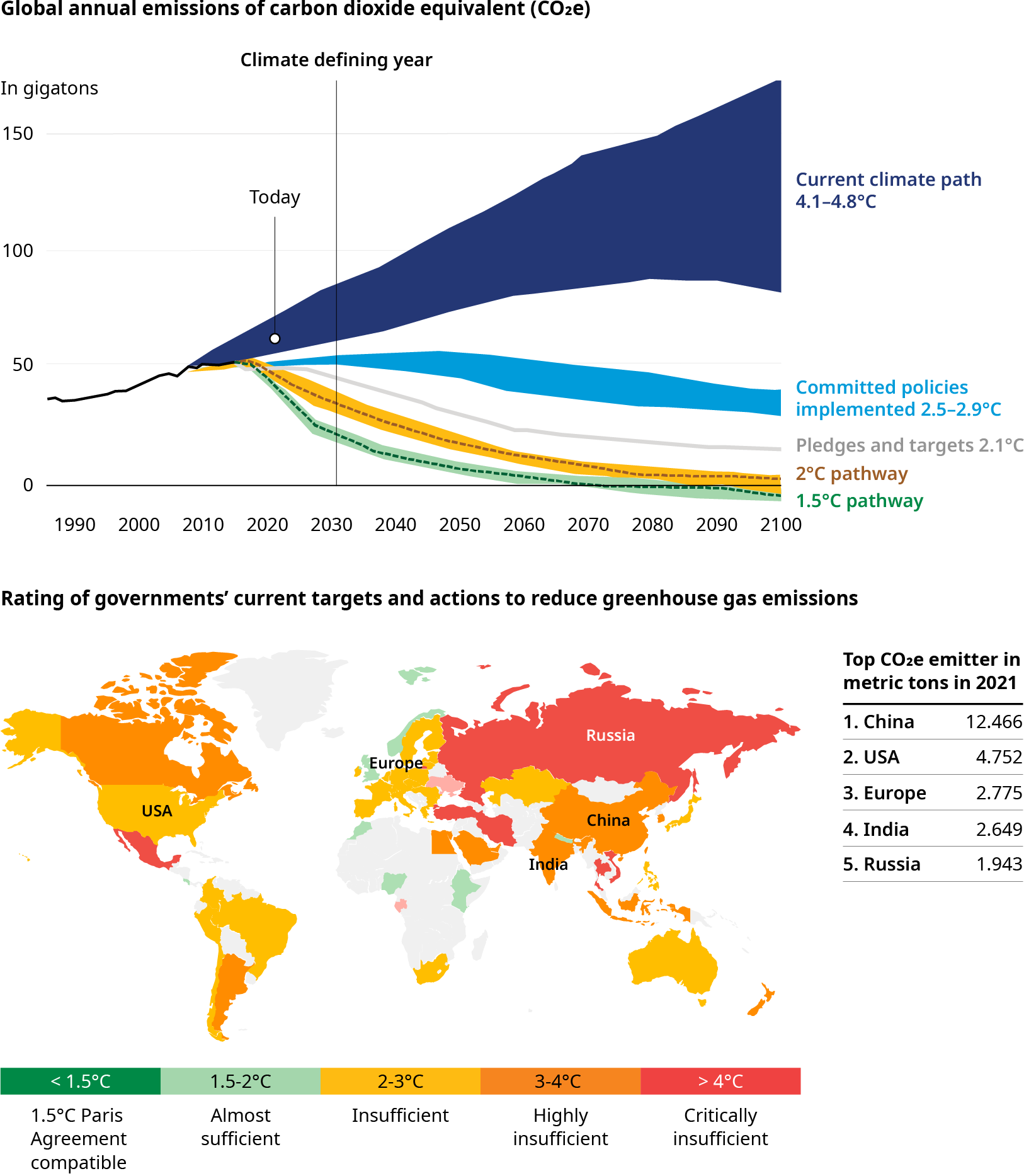

As things stand today, the global economy is not on track to hit the 2015 Paris Agreement’s target of keeping the Earth’s temperature rise to about 1.5 degrees Celsius over pre-industrial levels. In fact, based on our current trajectory, the planet will be lucky if the increase can be kept at four degrees — global warming that would likely doom millions of people and species. Current calculations put us on track for an increase of between 4.1 and 4.8 degrees C.

Exhibit 1: Estimated global average temperature increase in 2100 based on annual greenhouse gas emissions scenarios

Source: Climate Action Tracker (2022). 2100 Warming Projections: Emissions and expected warming based on pledges and current policies. November 2022. Available at: https://carboncredits.com/h2-green-steel-production-191m-funding/. Copyright 2023 by Climate Analytics and NewClimate Institute, Oliver Wyman analysis

Even if countries were to live up to their pledges to cut

emissions, which they haven’t so far, the best possible

outcome would be an increase between 2.5 and 2.7 degrees C.

That would significantly amplify the frequency and severity of

global warming effects, such as heatwaves, droughts, extensive

melting of polar ice, and wildfires already plaguing the

planet today at only 1.1 degrees C higher than pre-industrial

times.

Why can’t we solve the problem? The global economy’s lack of

progress is in large part because government and industry are

demonstrating insufficient urgency and failing to prioritize

those solutions that will produce the biggest reduction in

emissions. They are failing to address climate change the way

they took on the COVID-19 pandemic, maybe because the solution

is far more complex. Where development of vaccines provided a

silver bullet to attack COVID globally, climate change has no

one solution applicable to the entire global economy or any

region.

But we could prioritize our most productive options, providing both regulation and incentives to ensure adequate capacity is built and commercially sustainable. At the top of that list should be an expansion of renewable energy technologies, the upgrading of electrical grids, and the rapid phase out of the biggest polluters — coal and lignite being prime examples — in electricity generation.

A straightforward but expensive solution

Currently, the energy industry is the biggest producer of greenhouse gas emissions that cause climate change, but it also holds the key to a solution that would get the economy back on the path to 1.5 degrees C. The immediate answer to the impending climate catastrophe would be the investment of at least $20 trillion into renewable energy and the infrastructure to support it.

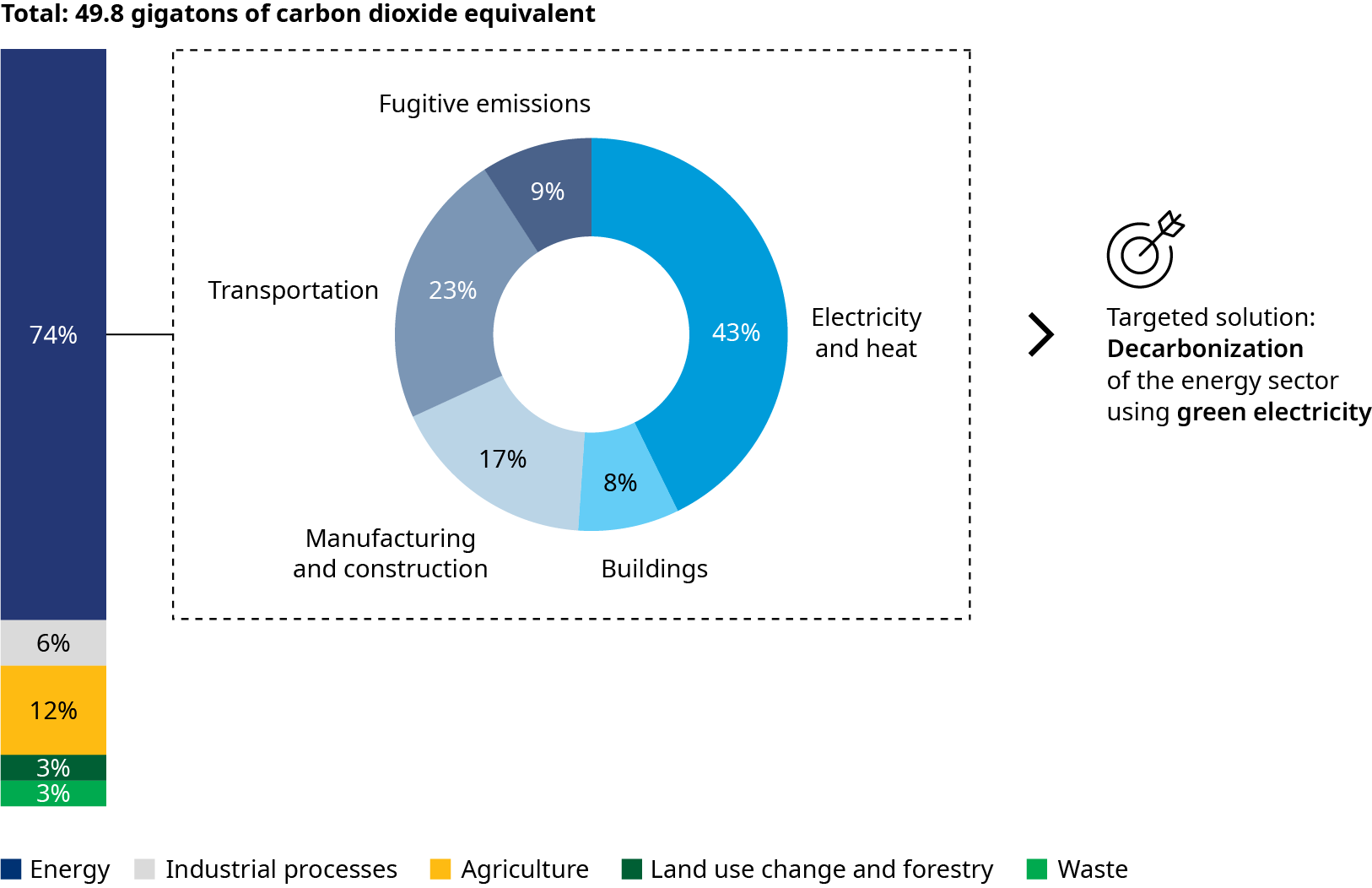

Exhibit 2: World Greenhouse Gas Emissions in 2021

Source: Climate Action Tracker (2022). 2100 Warming Projections: Emissions and expected warming based on pledges and current policies. November 2022. Available at: https://carboncredits.com/h2-green-steel-production-191m-funding/. Copyright 2023 by Climate Analytics and NewClimate Institute, IEA (2022), CO2 Emissions in 2021, IEA, Paris https://www.iea.org/reports/global-energy-review-co2-emissions-in-2021-2, License: CC BY 4.0, Oliver Wyman analysis

By our calculations, that investment would keep Earth’s

temperature rise below two degrees by expanding low-carbon

electricity generation capacity by 340% by 2030 and phasing

out coal and lignite that same year. Those changes would mean

that the bulk of global electricity generation would be from

green sources. While renewable capacity is

expected to grow about 32% in 2023, that expansion would only

match the anticipated increase in

electricity demand and mean essentially no improvement in

emissions.

In 2022,

global

energy-related carbon dioxide emissions grew almost

1%, representing an additional 321 million tonnes. This

established a record high of almost 37 billion tonnes sent

into the atmosphere that year, according to the International

Energy Agency (IEA). That was less than expected, given the

spike in the use of coal when global energy markets were

upended last year amid the Russian invasion of Ukraine and the

relentless demand for energy as the COVID-19 pandemic waned.

But while the overall percentage rise was smaller than both

2021’s increase and 2022’s 3.2% worldwide economic growth,

emissions need to fall — and soon — before the global economy

can declare progress against global warming.

The IEA called for a tripling

of renewable energy capacity recently as well as scaling up

clean energy technologies to drive down demand from the global

economy for fossil fuels. The intergovernmental organization

added that doubling progress on energy efficiency efforts

would also be necessary.

The number 1 source of emissions

While utilities have made progress in recent years

incorporating more renewable and clean energy sources, there

is currently not enough supply to allow most electricity to be

produced by clean energy. Quite the contrary, more than 40% of

global electricity is still produced by burning coal, which is

only a few percentage points below what it was in 2010.

Renewables only fill in the gaps to cover higher electricity

demand. In places like India, China, and Europe, coal use rose

in 2022 in response to rising natural gas prices — with

India’s use up 10% and Europe’s and China’s up 5%,

according to the World Bank.

In almost every country today, electricity and heat generation

are responsible for the largest share of greenhouse gas

emissions — 43% of the global total. In 2022, just short of

30% of electricity generated globally is from renewable

sources. While total replacement of fossil fuels is probably

not an optimal — or even feasible— answer, countries should

invest in strategies that allow them to eliminate over the

short term the use of coal, lignite, and oil in electricity

generation.

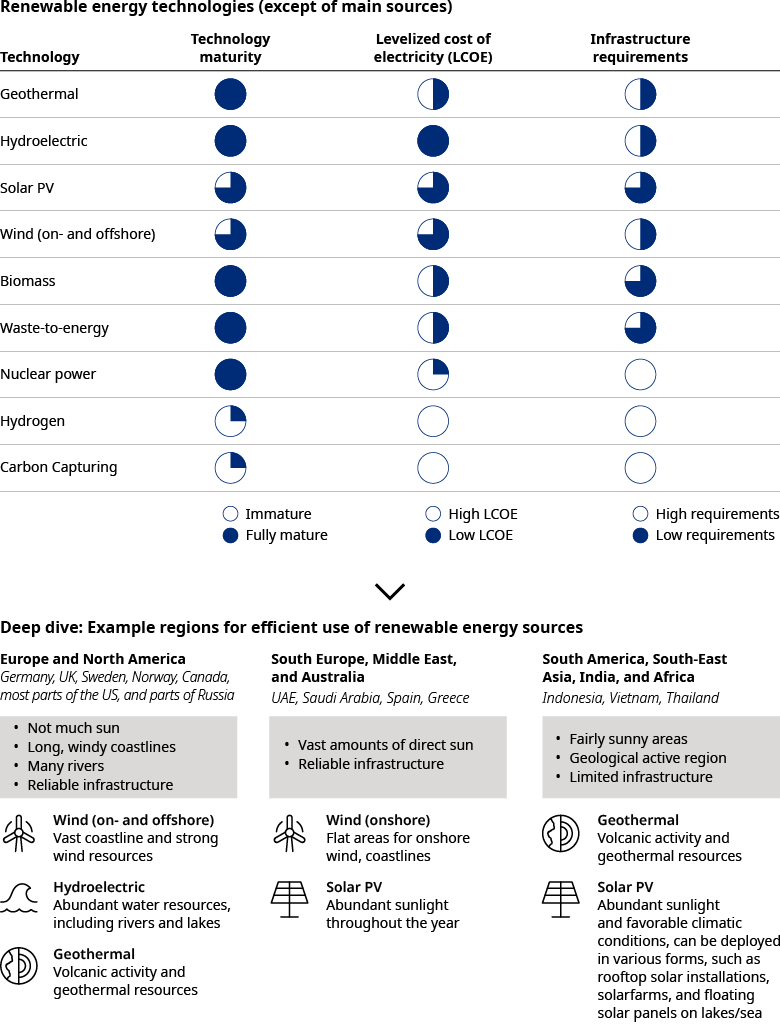

Some of the key technologies to replace fossil fuels are

already out there and well established, such as hydro, wind,

nuclear, and solar power. And there are other technologies,

such as green hydrogen, still trying to find a workable

business model. In 2022, the rise in CO2 emissions would have

been 550 million tonnes bigger had it not been for the

increased deployment of clean energy technologies,

the IEA

noted in 2023.

Exhibit 3: Overview of renewable energy sources

Note: Levelized cost of electricity is the average net present

cost of electricity generation for a generator over its

lifetime

Source: Oliver Wyman analysis

The cost of decarbonization

Between now and 2030, an investment of $20 trillion, or about

20% of the global gross domestic product, would produce enough

renewable energy capacity, storage, and grid extensions to

reduce emissions by 12 gigatonnes of CO2 equivalent, we

calculated. That would include an increase of about 730% in

solar capacity, 410% in wind, and 48% in hydro and put the

world on a path to a temperature rise of below 2 degrees C.

CO2 equivalent, or CO2e, refers to the number of metric tons

of CO2 emissions with the same global warming potential as one

metric ton of another greenhouse gas, such as methane or

nitrous oxide.

No doubt, it is a sizable investment: The yearly spend would

need to increase six times beyond what we are spending

annually today. But without a significant increase in spending

on renewables — primarily on wind and solar — there’s no hope

of reaching net zero or keeping the temperature rise below 2

degrees. Our research also notes that some of the investment

should be happening at the consumer level through small-scale

residential photovoltaic and storage solutions, for example.

Without this kind of investment, other industry efforts to

decarbonize will also stall: There is simply not enough

renewable energy to generate both electricity and heat for

global grids and fuel industrial decarbonization. For

instance, steel producers can’t consider switching to green

hydrogen from high-carbon coal to any significant degree until

there is sufficient renewable energy to produce the requisite

amount of hydrogen needed by the industry.

If renewable energy is switched from producing electricity to

industrial uses, it would end up pushing utilities to use more

coal, oil, and natural gas. In a very real way, the lack of

renewable energy is holding up decarbonization in a whole host

of industries.

Regional differences

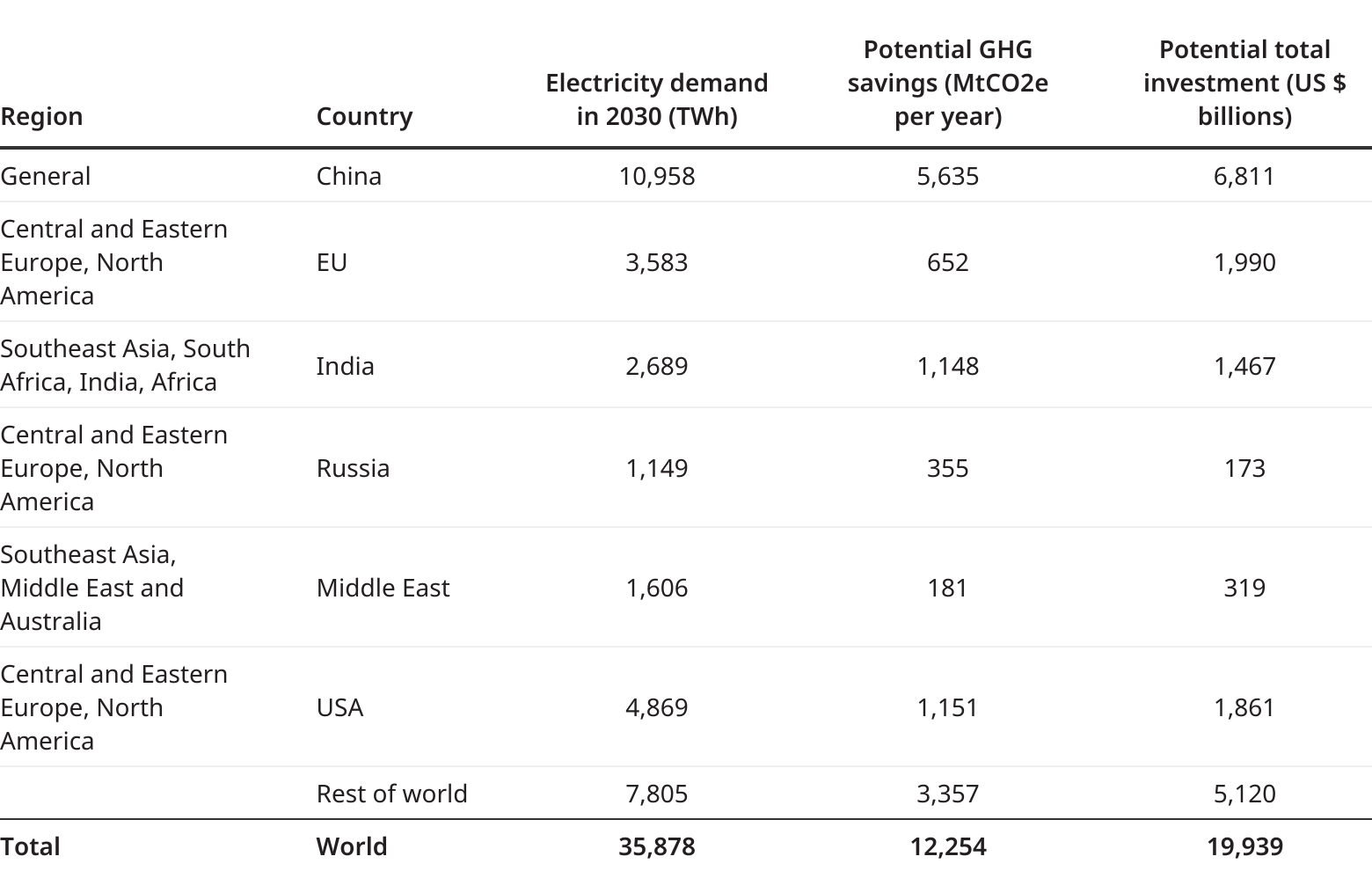

Three of the largest emitters would have to make the biggest investments: China would need to invest almost $6.8 trillion; the United States, $1.9 trillion; and the European Union, almost $2 trillion. But the potential savings in GHG emissions from these three regions could amount to a little over 7.4 billion tonnes of CO2 equivalent a year.

Exhibit 4: Potential investment requirements to replace fossil fuels with leading renewable energy

Note: Electricity demand is measured in terawatt-hour(TWh).

The potential greenhouse gas savings are measured in metric

tons of carbon dioxide equivalent(MTCO2e) and refer tothose

that are currently emitted from electricity production by

fossil fuels.

Source: IEA (2022), World Energy Outlook 2022, IEA, Paris

https://www.iea.org/reports/world-energy-outlook-2022, License: CC BY 4.0

(report); CC BY NC SA 4.0 (Annex A), IEA

(2022), CO2 Emissions in 2021, IEA, Paris

https://www.iea.org/reports/global-energy-review-co2-emissions-in-2021-2, License:

CC BY 4.0, IRENA (2022), Renewable Power

Generation Costs in 2021, International Renewable Energy

Agency, Abu Dhabi, Oliver Wyman analysis

From a technology perspective, regions will make different

choices about which renewable energy option to pursue. For

instance, in the US and much of Europe, the investment should

be concentrated on exploiting their long windy coastlines and

potentially geothermal resources. In southern Europe, the

Middle East, and Australia, the emphasis should be on their

vast amounts of year-round sun.

The next seven years will be critical for our survival as we

know it today. Governments and industry talk about reaching

net zero by 2050, but that work must start today and with

investment in renewable energy.

Catrin Ciemer, Magnus Beyer, and Robert Famulok contributed to this article.